Back when I first started doing home inspections, I was under the impression that roof ventilation was the cure-all for everything. I would look at a lot of problems and quickly point to insufficient roof ventilation as the cause, and I’d recommend more roof ventilation as the cure.

Blistered shingles? Not enough roof ventilation.

Ice dams? Not enough roof ventilation.

Frost in the attic? Not enough roof ventilation.

Today I’m much more ho-hum on roof ventilation. Asphalt shingle manufacturers require roof ventilation to help preserve the life of shingles, despite the fact that the color of shingles will have a greater effect on their life expectancy than roof ventilation will. Here’s an excerpt from Joseph Lstiburek in his article Info-015: Top Ten Dump Things To Do In the South:

Lets now talk about durability of shingles and shingle temperature. Venting or non-venting a roof has about a 5 percent impact on shingle temperature and roof sheathing temperature and even less on shingle durability. The color of the shingle is more important than venting or non-venting.

An attic with insufficient ventilation will get warmer than a well-ventilated attic, which may increase the temperature of the shingles, which may decrease the life of the shingles… just a little. Proper ventilation will also help to keep the attic space cooler during the winter, which reduces the potential for ice dams. But let me be clear on this: proper roof ventilation does not prevent ice dams. It just nudges you in the right direction. The same thing goes for frost in the attic; as I mentioned in a previous post about frost in the attic, proper ventilation may reduce frost accumulation in attics, but it won’t prevent it.

In other words, roof ventilation isn’t a cure for any condition, but it’s still required. Roof vent manufacturers publish installation instructions that are easy to read and should be easy to follow, and roof ventilation is required in section R806 of the building code, but a lot of folks either don’t read the instructions or don’t understand them. Today I’ll cover some of the most common roof vent installation issues we come across as home inspectors.

Mixed Exhaust Vents

For proper ventilation, both high and low vents should be installed. On paper, high vents are supposed to act as exhaust vents while low vents should act as intake vents. Convection is supposed to help make this happen. In reality, it all depends on how the wind blows, convection has little to no effect, and it’s never perfect. The intake vents will typically be soffit vents, while the exhaust vents may consist of ridge vents, turbine vents, box vents, or powered vents… but only one of those. The photo below shows an example of these different types of vents, all installed on the same roof, which is a no-no.

When different types of roof vents are installed, there is an increased potential for air in the attic to basically short-circuit. In the photo above, the power vent would probably end up sucking in air from all of the other high vents in the photo, while pulling in just a small amount of air from the lower soffit vents. The solution here is to install only one type of exhaust vent.

Power Vents

Power vents shouldn’t be used because they create more problems than they fix. I blogged about them many years ago: Attic Fans Won’t Fix Ice Dams (or anything else). I use the terms ‘attic fan’ and ‘powered roof vent’ interchangeably, as well as ‘roof vent’ and ‘attic vent’.

Crooked Turbine Vents

I’ve never been a huge fan of turbine vents because I have it in my head that they may end up causing some of the same problems that powered roof vents do, but the fine folks at Complete Building Solutions swear by ’em, and I trust those guys, so I won’t complain about turbine vents. The one thing I’ll mention is that turbine vents need to be installed perfectly level; when they’re not installed level, they don’t turn. In the photo below, the vent on the left wasn’t level. Do you see anything else that’s wrong in the photo?

The other thing about turbine vents is that they really do pull air out of the attic. If air sealing hasn’t been performed in the attic, turbine vents will pull air into the attic from inside the house, and shouldn’t be used. That bears repeating: do not install turbine vents if the attic has not been professionally air-sealed.

Insufficient intake vents

Current standards specify a 50/50 split between high vents and low vents, but how are low vents supposed to be installed in a house with no soffits?

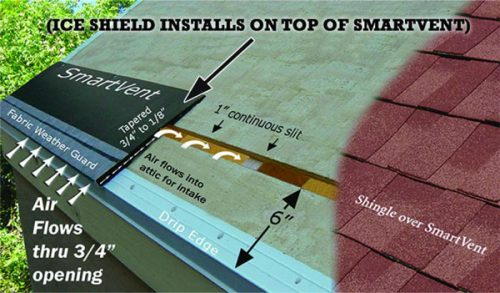

Without any low vents, the high vents will tend to pull conditioned house air into the attic through attic air leaks. One solution would be to install special vents cut down low into the roof, such as SmartVents™, shown below.

Another less desirable option would be to install a bunch of box vents low down on the roof. I could go on and on with these roof vent installation errors or shortcomings, but I never make a huge deal about any of this stuff because I don’t think it makes a ton of a difference. Focus on sealing attic bypasses before addressing ventilation. Ventilation mostly helps to hide other problems.

For more reading material on roof ventilation, check out the links below:

- Green Building Advisor: All About Attic Ventilation – this article looks at all of the reasons that attic venting is required, and goes on to say they’re all ho-hum reasons. I completely agree.

- Building Science Corporation: Understanding Attic Ventilation – a discussion of vented vs. unvented attics.

- Building Research Council-School of Architecture: Early History of Attic Ventilation – A long explanation of why our current rules for attic ventilation are arbitrary. This is a fascinating read which starts out by explaining “The attic ventilation ratio “1/300” is an arbitrary number selected by the writers of FHA (1942) with no citations or references”.

Harry Janssen

November 9, 2021, 8:12 pm

The flashing on the vent is wrong