High-efficiency furnaces use PVC pipes to vent the exhaust gases out of the home, and manufacturers are very specific about how the installation should be done. As a home inspector, how far should I go to make sure the vent is properly installed? Of course, I’d report on a vent that wasn’t vented to the outdoors. But what about a vent that terminates too close to an openable window? Maybe, right? And what about a vent that has too many elbows? I think this is where a lot of home inspectors start to shake their heads and say that this goes beyond our standard of practice… but why?

I won’t tell you exactly what a home inspector should or shouldn’t report on, but I will cover some of the most common defects that we come across as home inspectors.

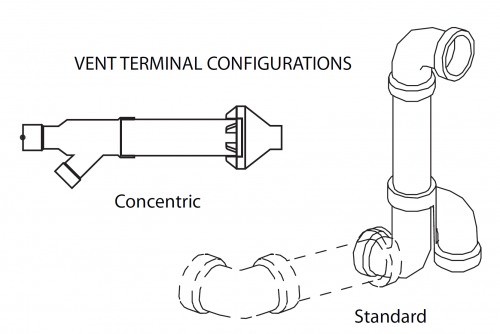

Vent Terminals: keep them separate

Most high-efficiency furnaces have two pipes coming out of the wall; one to bring combustion air into the furnace and the other to blow exhaust gases back out. It’s important for the exhaust gas to not get sucked back into the furnace, so manufacturers will usually give several ways to do this. One way is to make the exhaust terminate higher than the intake, usually by at least one foot. The warm exhaust gas rises, which prevents it from being sucked back into the intake.

Sometimes you’ll find a reducer at the terminal, which helps to increase the velocity of the exhaust gases. This also helps to get them out and away from the intake. Yet another way to terminate these pipes is to use something called a concentric vent terminal; this makes for a little bit cleaner-looking installation at the exterior because there’s only one single pipe exiting the wall. The intake and exhaust pipes join together inside the home, and the exhaust blows out the front while the intake brings air in from the backside.

When a two-pipe system is used, I make sure that the exhaust is not pointed down, and that the exhaust is not located below the intake. The simple way to do this is to run the furnace and check the exhaust at the exterior; even if the pipes are labeled, installers sometimes get them reversed.

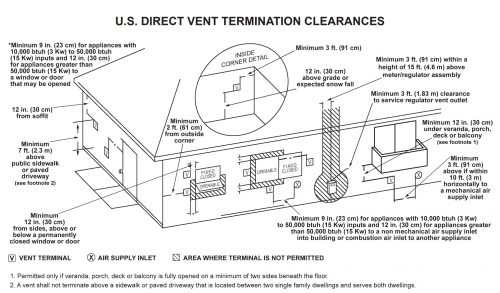

Vent Terminal Clearances

With a two-pipe system, also known as a direct vent, you’ll find very similar rules from manufacturer to manufacturer. You can find some version of the diagram below in almost every furnace installation manual, and it nicely illustrates these clearances.

There’s a lot of stuff covered in this diagram, but here are some of the most common offenses. The vent must terminate at least:

- One foot from windows and doors

- Three feet from inside wall corners

- One foot above the ground, and ideally one foot above the anticipated snow level

- One foot below porches, balconies, and decks

If you have a single-pipe (non-direct vent) system, it means the furnace takes combustion air from inside the house. Because of this, the rules are more strict when it comes to clearances around windows and doors, but they’re not wildly different.

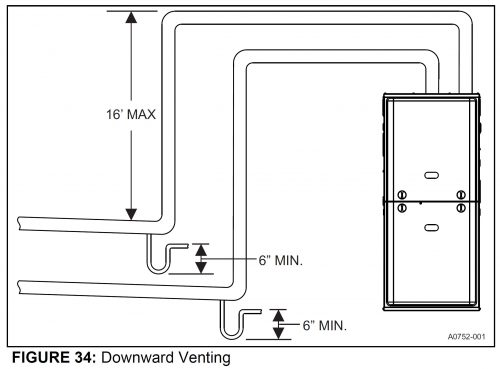

Vent Pitch

Vents should be pitched so condensate will drain down into the furnace. There should be no flat sections of venting, no dips, and no sags… but never say never. I recently ran across some installation instructions that actually allowed this, provided a drain was installed at the low point.

I’ve never actually seen this done, but it makes perfect sense. And the vent should never pitch downward away from the furnace towards the outdoors because this can lead to big, unintentional ice sculptures during the wintertime.

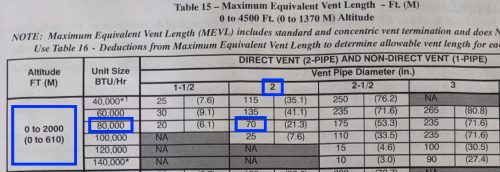

Vent Sizing

Every furnace installation manual has a bunch of daunting tables to figure out what size pipe is needed. They consider the altitude, the furnace size, the length of pipe, the number of elbows used, and the type of elbows used. I don’t make a habit of trying to figure all that stuff out and do all of those calculations. Instead, I use this general guideline: if the furnace is 80k BTUs or smaller, 2″ pipes are probably fine. If the furnace is 100k BTUs or larger, we probably need 3″ vent pipes.

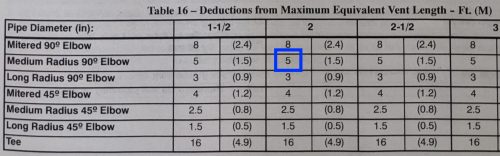

A few yellow flags that would make me question the vent size would be a 100k BTU+ furnace with a 2″ pipe, or a pipe with an unusually long equivalent length. The equivalent length factors in the overall length of the pipe, as well as the type and number of elbows used. The photo below shows a good example of a furnace installation that we recently questioned.

It’s quite clear that the humidifier was installed after the furnace, and the installer had to make a bunch of extra bends in the venting to make room for it. This was a fairly large house, which meant that had to be a fairly large furnace, which made us wonder if the 2″ venting was large enough. So we pulled out the installation manual and looked it up.

As it turns out, this was only an 80k BTU furnace. The manufacturer allows for 70′ of piping, subtracting somewhere between 3 and 8 feet for every 90, depending upon the type of 90.

There was a mix of 7 medium and long sweep elbows (3 not pictured), but just to be quick and conservative, we assumed they were all medium sweeps, so we calculated a total of 35′ for the elbows. Add the remaining rise to the ceiling and then out of the wall, and we had far less than the maximum allowable length.

In other words, there was no problem here. But if this had been a 100k BTU furnace, the elbows alone would have been enough to need 3″ venting. This is a good exercise to go through when we see something out of the ordinary, and it only takes a couple of minutes.

Robert Hall

May 31, 2022, 10:11 am

We have a cabin with a high-efficiency furnace that also serves as the hot water heater so it runs year round. Our particular problem was that the furnace was installed without regard to the foliage next to the cabin and within a month the leaves from a broad-leaf bush were sucked in and blocking the intake. Relocating the bush solved the problem.