Buying a home with aluminum wiring? The seller will probably tell you it’s perfectly fine, has never been a problem, and there’s nothing to worry about. We’ve heard this story many times. I blogged about this topic many years ago, but it’s time to revisit this topic.

Here at Structure Tech, we teach a ton of continuing education classes to real estate agents. For our Home Inspection Horrors class, we cover the known hazards with aluminum wiring and the options for repair. During a recent class, we had a real estate agent question the need for anything to be done about aluminum wiring, taking that stance that this is a perfectly good product with a bad reputation. That’s not the case.

What is aluminum wiring?

Aluminum wiring is still used today, and there’s nothing inherently unsafe about it. The service wires coming into homes consists of aluminum wiring, and there are plenty of aluminum 240-volt circuits in use today. That stuff is all fine. The stuff that could be unsafe, the stuff that had problems, was a specific alloy used during a specific time, and that’s what this blog post is all about.

For the rest of this post, when I refer to aluminum wiring, I’m referring to aluminum branch circuit conductors installed from approximately 1965 to 1972. “Aluminum branch circuit conductors” means wires that feed 15- and 20-amp circuits in houses. It’s the wire that connects to outlets, switches, lights, and the like. That stuff had a lot of problems.

What’s the problem?

Here are a few key points about aluminum wiring, which comes from three authoritative documents at the end of this blog post:

- Aluminum wiring starting being used in single family homes as a replacement for copper wiring around 1965.

- Between 1965 and 1972, over two million homes were wired with aluminum. There are homes all over the Twin Cities with aluminum wiring.

- Many homes caught fire and people died as a result of aluminum wiring causing fires.

- The Franklin Research Institute determined that pre-1972 homes wired with aluminum were 55 times more likely to reach “fire hazard conditions” than homes wired with copper.

- Aluminum wiring failed at the connection points, such as splices between wires, connections at outlets, circuit breakers, switches, lights, etc.

- In 1972, the formula for aluminum wiring changed, making it a much safer product. Aluminum wiring was used in single family homes for a few years after that, but was completely phased out by the mid-’70s.

The problem with aluminum wiring is that it expands and contracts at a high rate, which can lead to loose connections. Connections between aluminum and copper can also cause oxidation, resistance, heat, increased expansion… you get the picture. All of that can lead to a fire.

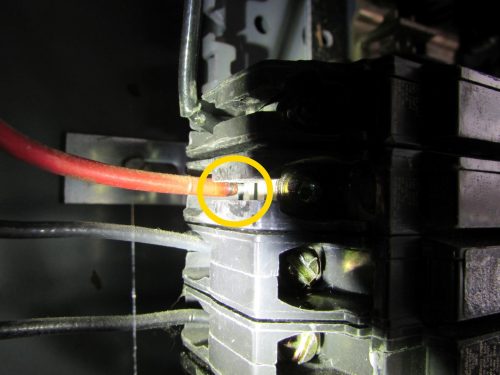

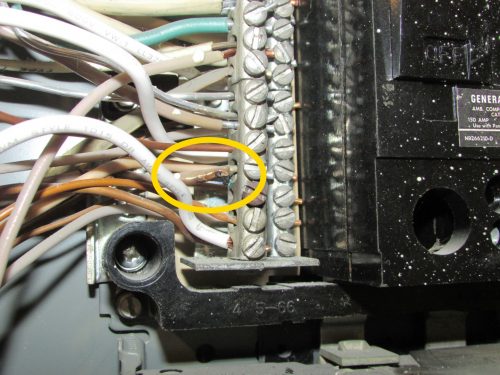

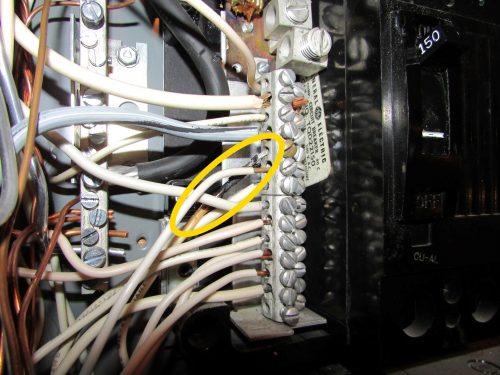

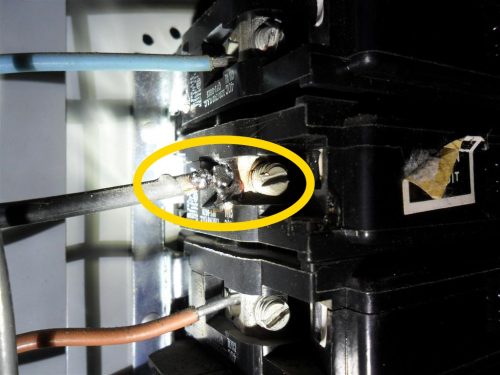

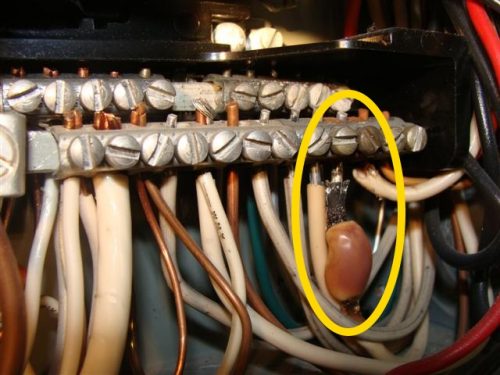

Scorched wiring

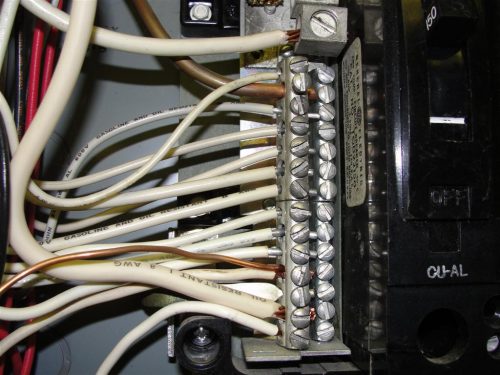

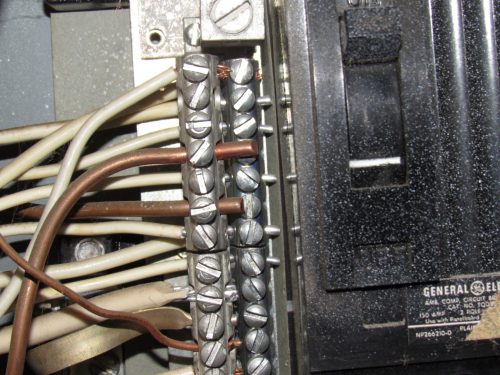

Here’s an assortment of scorched aluminum wires that we’ve found during our home inspections. These constitute “fire hazard conditions”.

We find aluminum wiring during our home inspections about once a month. I estimate that a quarter of those homes have scorched wires in the panel, but I can’t comment on the rest of the wiring. Home inspectors do not pull outlets and switches out of the wall, because there’s a lot that could go wrong.

If we did, however, I’m guessing we’d find a lot more scorched wiring.

If it hasn’t burned down yet, it’s safe. Right?

There’s a persistent myth that if a home was wired with aluminum 50 years ago and no fires have started, it’s safe. The problem with this assumption is that when new owners move in, they will put different demands on the system. With a change in occupancy comes a change in use, and that’s when problems often show up.

Past performance does not predict future performance.

Monitor for problems? No.

Some home inspectors will recommend “monitoring” aluminum wiring for signs of problems. I take issue with this recommendation because I don’t know how a homeowner is supposed to do that. Make sure the outlets don’t start on fire? Pull outlets out of the wall once a month and carefully inspect the connections for overheating? Get out.

I don’t know what it means to monitor aluminum wiring for problems, and I don’t think most homeowners do either. Not only that, but the Consumer Product Safety Commission (CPSC) says that “failing aluminum-wired connections seldom provide easily detected warning signs.”

Repair Methods

The CPSC lists three potential repairs for homes with aluminum wiring: individual repairs with COPALUM connectors, individual repairs with AlumiConn connectors, or complete replacement of the aluminum wire. You can read about how the individual repairs would be made here: Aluminum Wiring Repairs.

COPALUM

Individual repairs with COPALUM connectors is not a viable option for Minnesotans. This requires the use of a specialized product that needs to be installed with a specialized tool, by a certified COPALUM Retermination Contractor. I contacted the company that provides this product and was informed that there is not a single certified contractor in Minnesota. So that’s out.

AlumiConn

It’s possible to make individual repairs with AlumiConn connectors. This involves pigtailing aluminum wires to copper wires at every place the wires begin and end. The aluminum and copper wires get connected together with this specialized connector, but it’s expensive.

Amazon sells a 10-pack for $45, and the price goes down when ordering in bulk quantity. Not only is the product expensive, but it’s a ton of work. Every receptacle needs to be pulled and re-wired. Every switch. Every junction box. Every everything.

Not only that, but have you ever replaced an old outlet and had a difficult time getting the wires to fit back into the box properly? Just imagine at least three of these devices and twice as much wire at every box.

Besides the fact that this repair method is expensive, there’s a chance that the repairs could be incomplete. Will every single junction box be found? Maybe, maybe not. Seattle home inspector Charles Buell shared a story some time ago about how he was hired to check on some repairs that were made at a home that he had previously inspected, and he found at least one junction box and one light fixture that had been missed. You can read about it here: incomplete aluminum wiring repairs.

Replacement

The surest and most complete repair is to have aluminum wiring replaced. This leaves very little to chance and doesn’t leave the home with a bunch of repair methods that the next semi-qualified homeowner might accidentally mess up. The obvious drawback to this is the expense involved. Of course, the expense depends on how much aluminum wiring is present and will vary greatly from house to house. This is where the electrician comes in.

If you’re buying a home with aluminum wiring and you hire an electrician to inspect and/or repair the wiring, make sure they have experience with aluminum wiring repairs.

How to identify aluminum wiring?

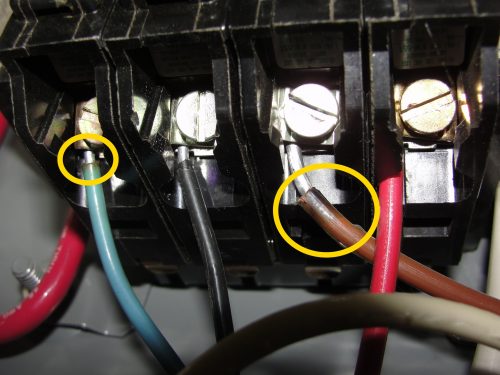

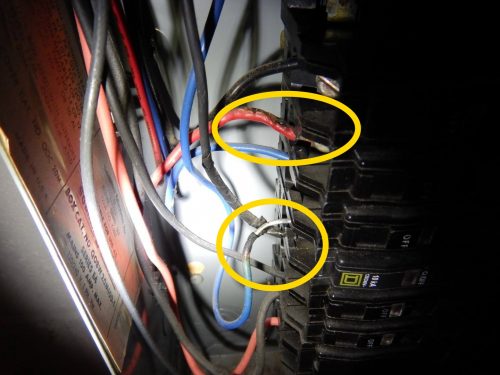

The easiest and most obvious place to find aluminum wiring is inside of the main electric panel. The pictures below show a mix of aluminum and copper wiring inside of the panels.

Just watch out for tin-coated copper wiring. This looks similar to aluminum wiring, but it wasn’t used during the same period of time, wasn’t increased in size like aluminum is, and typically had a cloth jacket around. This is not aluminum wiring.

Aluminum wiring can sometimes be seen by removing cover plates at outlets and switches.

Every once in a while, we’ll find aluminum wires with uncapped splices. Don’t ask me why. We’ve just found them. People do crazy things.

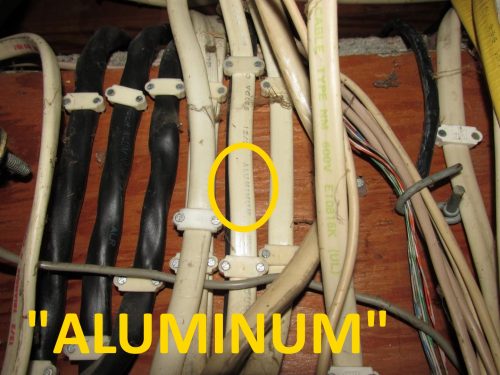

And finally, the least reliable method but still a good one, is to read the writing on the non-metallic sheathed cable. Specifically, look for the 10- and 12-gauge wires. Aluminum wiring will be marked as such.

Conclusion

If you’re buying a home with aluminum wiring, have a thorough inspection of the wiring performed by an electrician and repairs made if needed. This inspection will require the inspection of at least a representative number of connections. This means pulling outlets out of the wall, pulling switches out of the wall, taking lights down to inspect the connections, pulling wires out of junction boxes, etc. If any connections aren’t proper, repairs should be made.

For some more detailed discussions regarding the specific hazards with aluminum wiring, here are some excellent related documents:

- Aluminum Wiring Repair – from CPSC

- Aluminum Wiring – by Douglas Hansen

- Reducing the Fire Hazard in Aluminum Wired Homes – by J. Aronstein

Rick Sniders

April 30, 2019, 6:25 am

If I were to find aluminum, could you pigtail new copper and solder old & new together before putting on caps? Curious.

Reuben Saltzman

April 30, 2019, 9:52 am

Hi Rick,

No, that’s not listed as an approved repair method.

Acton Brovest

April 30, 2019, 9:10 am

Ideal sells a purple Twister Al/Cu Wire Connectors that they are marketing as a solution for splicing aluminum to copper. What are your thoughts on this product? Thanks.

Reuben Saltzman

April 30, 2019, 9:57 am

Hi Acton,

The short answer is that pigtailing with the Ideal 65 Twister is not a recommended repair. The CPSC does not recognize this repair method, and there’s a lot of information about this in J. Aronstein’s article, which I linked to at the end of this post. I’m copying the information word-for-word below:

“D. PIGTAILING USING IDEAL #65 “TWISTER” CONNECTOR

After about 1987, when UL adopted a revised standard (UL486C) applicable to

twist-on connectors for aluminum wire, twist-on connectors were no longer being

marked (in the USA) as UL listed for aluminum wire applications. In 1995, UL

accepted a twist-on connector – the Ideal #65 “Twister” – for aluminum-to-copper

wire combinations, including those commonly used in the “pigtailing” retrofit.

The Ideal #65 has been heavily promoted for that application. The connector is

essentially the same as twist-on connectors that had performed poorly in

previous testing, the major difference being that it is pre-filled with

inhibitor compound. Based on its construction, there is good reason to question

the long-term performance of the Ideal #65. Because of its UL listing, however,

most electrical inspectors would accept this connector for pigtailing of

aluminum wiring.

As soon as it appeared on the market, the Consumer Product Safety Commission

(CPSC) questioned UL’s listing of this connector for the aluminum wire

pigtailing wire combinations. Although the manufacturer claims that the

connector has been thoroughly tested for the application, neither the

manufacturer or UL have released any detailed test data. The manufacturer

states that the connector has received CSA certification for the same wire

combinations. Information developed so far indicates the following:

– The manufacturer did not initially claim that the connector is

intended for use in the pigtailing retrofit application. Instead,

the manufacturer stated (to CPSC) that the Ideal #65 is intended for

such applications as connecting lighting fixtures and ceiling fans.

Ideal’s engineering manager at that time committed to CPSC to change

their its advertising and instructional information accordingly, but

Ideal has not followed through on that commitment.

– UL did not independently perform the “heat-cycle” life tests

required by their standard. These tests were performed by the

manufacturer, with UL accepting the manufacturer’s results.

– The connector was not “heat-cycle” tested for the common

pigtailing wire combinations with current passing through the

aluminum-aluminum wire path (in an aluminum-aluminum-copper splice).

– The “heat-cycle” tests that were performed by the manufacturer on

the Ideal #65 “Twister” connector were not done using aluminum wire

of the type actually installed in homes built in the 1960’s and

early 1970’s.

– The CSA certification was based on UL’s acceptance for listing.

CSA did not independently evaluate the Ideal #65 connector. In

fact, the use of a zinc-plated steel spring in the connector

violates a CSA general requirement for connectors for aluminum

wiring.

– The inhibitor compound/plastic shell of the connection in

combination can ignite readily and burn freely. This increases the

chance of fire ignition if connection failure occurs.

Independent testing of the Ideal #65 “Twister” has demonstrated the

following:[11]

– Installed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (without abrasion

or pretwisting), the connector does not reliably establish

low-resistance connections. (This finding contradicts the

manufacturer’s claim that particles in the inhibitor inside the

connector serve to abrade the wire and eliminate the need for separate

abrasion of the wires.)

– The Ideal #65 connector does not consistently pass the UL “heat-cycle”

test requirement when tested with aluminum wire of the type actually

installed in homes with current passing through the aluminum-aluminum

path in a pigtailing (aluminum-aluminum-copper) splice.

– The performance of the Ideal #65 Twister is essentially the same as

that of poorly-performing twist-on connectors previously evaluated

for the aluminum wire pigtailing application.

Additionally, field burnouts have now been reported with the Ideal #65

connectors in their rated applications. With CPSC skeptical (and requesting

that UL withdraw its listing), the manufacturer initially agreeing that the

connector is not for the pigtailing retrofit application, independent tests

clearly demonstrating poor performance, and field failures reported, the use of

the Ideal #65 “Twister” connector for the pigtailing application is definitely

not recommended. If the COPALUM repair is not available, use the AlumiConn

connector (See Section 1C).”

Chris Johnson

May 1, 2019, 3:32 am

I just moved into my home a few months ago, half the house is copper, the other half is aluminum, I got a permit, installed a new braker box and for every 15 and 20 amp breaker I used a Cafci breaker. Is my home safe now?

Reuben Saltzman

May 1, 2019, 4:34 am

Hi Chris, combination arc-fault circuit breakers (CAFCIs) will certainly reduce the potential for a fire. Nevertheless, I wouldn’t say that doing this makes your home safe. If that’s all that it would take, this would certainly be the preferred solution, as this method is far less costly than all of the other repair methods listed by the CPSC.

I recommend you have an electrician inspect your entire electrical system for safety, and let them determine whether it’s safe or not.