Yes, you read that right. I’m thankful for closed cell foam insulation. Of course, I’m thankful for my family, health, and all that other jazz, but this is a blog about home inspections and home related topics, so I’m going to stay focused on that. To fully explain why I’m so thankful for closed cell foam insulation, I first need to complain about my house a little bit.

My thirteen-year-old Maple Grove house has an unfinished basement with a walkout; this means about half of the basement walls have a poured concrete foundation, and the other half, the part that’s above grade, has conventional 2×6 wood framing. The foundation walls are insulated at the exterior with rigid foam; this is a great way to insulate a foundation, because it means that the concrete walls will be relatively warm, and the potential for condensation problems will be minimized. If you want to read more about foundation insulation methods, click this link – foundation insulation.

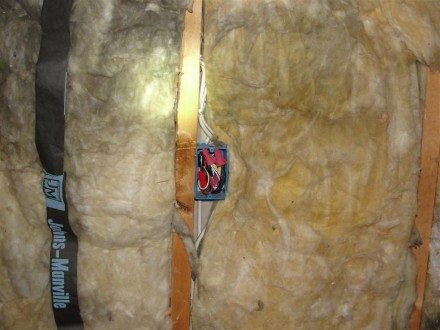

The stud walls, on the other hand, were insulated the same way as 99.9% of the houses in Minnesota – with fiberglass batts. Yuck. While this is the standard way to insulate a wall, it’s also probably the worst acceptable way to insulate a wall. The photo at right gives a great example of how fiberglass batts are installed incorrectly all the time; just look at those gaps around the junction box. I’ve already dedicated a blog to complaining about fiberglass batts, so enough on that topic.

The stud walls, on the other hand, were insulated the same way as 99.9% of the houses in Minnesota – with fiberglass batts. Yuck. While this is the standard way to insulate a wall, it’s also probably the worst acceptable way to insulate a wall. The photo at right gives a great example of how fiberglass batts are installed incorrectly all the time; just look at those gaps around the junction box. I’ve already dedicated a blog to complaining about fiberglass batts, so enough on that topic.

In addition to having fiberglass batts for insulation, the vapor barrier in my basement was basically useless. Here’s how a vapor barrier is supposed to work: to prevent air from passing through the fiberglass insulation and creating moisture problems in the wall, a vapor barrier gets installed. This consists of 6 mil polyethylene sheeting (aka ‘poly’, aka ‘Visqueen’) that has been made airtight; that means caulked, overlapped, sealed, taped, etc. On a home built today, this will be done quite well. On a house that’s thirteen years old… no way. The vapor barrier will probably be just about useless.

Unsealed vapor barriers create heat loss. Just thirteen years ago, vapor barrier were never sealed. It was standard practice to just use a stapler to throw the poly on the walls and leave everything completely unsealed. This practice allows for air to constantly circulate within the fiberglass insulation, creating a convective loop, which means a lot of heat gets lost through the walls.

I have my ‘office’ set up in my unfinished basement, so I spend a lot of time in the basement. During the winter it gets very cold in my basement, despite the fact that I have 2×6 walls filled with fiberglass insulation. Last winter I kept an electric space heater under my desk to keep my toes from turning in to icicles.

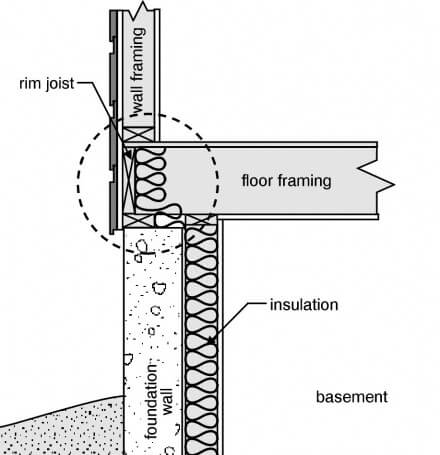

Fiberglass should never be used at rim spaces. The rim space is the area between the floors of a house; this is an area where it’s nearly impossible to install a proper vapor barrier. Without a vapor barrier, condensation can occur at the rim space, creating mold growth or eventually rotting out the rim space. This is why fiberglass insulation should never be used here. On new homes, it never is. The only type of insulation that gets used on new construction homes in Minnesota is closed cell spray foam insulation; we’ll come back to that in a minute.

Fiberglass should never be used at rim spaces. The rim space is the area between the floors of a house; this is an area where it’s nearly impossible to install a proper vapor barrier. Without a vapor barrier, condensation can occur at the rim space, creating mold growth or eventually rotting out the rim space. This is why fiberglass insulation should never be used here. On new homes, it never is. The only type of insulation that gets used on new construction homes in Minnesota is closed cell spray foam insulation; we’ll come back to that in a minute.

Unsealed vapor barriers can lead to mold growth. When a vapor barrier isn’t sealed and air is allowed to freely pass through the wall, what happens when warm, moist air hits a cold surface? It condenses. My basement stays relatively cool and dry throughout the year, so the vapor drive is really happening from the exterior during the summer. The walkout part of my basement faces south, so this part of the house is where I have the greatest temperature differential between the exterior and interior of the walls.

During the summer, as humid outdoor air passes through my walls and hits the relatively cool vapor barrier, the moisture condenses. This summer there was never enough moisture to actually drip down to the floor, but it was enough to leave drip marks in the insulation and allow mold to start growing between the insulation and the vapor barrier. This wasn’t major and I don’t have mold allergies, so I wasn’t too whipped up about this… but I couldn’t allow this to continue.

Enter closed-cell spray foam insulation. To address all of the insulation, mold, and vapor barrier issues at the same time, I had the wood framed walls in my basement completely re-insulated about three weeks ago. I had the vapor barriers removed, all of the fiberglass insulation removed, and closed cell foam sprayed in to the walls and rim spaces.

I love it. Closed cell foam acts as a perfect vapor barrier after 2″, it doesn’t allow for convection, and it has a much higher insulating value than fiberglass. Now when I walk down to my basement, I don’t feel a drastic change in temperature; my basement is only about two degrees cooler than the rest of my house. I can sit here at the computer without a space heater, and I no longer freeze my toes off. Life is good.

Having foam insulation sprayed in to the walls was expensive, but it was worth every penny. Will I ever get a payback in energy savings? I’m not sure. I didn’t even bother to check the numbers, because my main motivation for this project was comfort. Saving energy and not having mold growing inside the wall cavities is just a bonus.

Happy Thanksgiving.

Reuben Saltzman, Structure Tech Home Inspections – Email– Maple Grove Home Inspector